Why some beetles like alcohol

04/09/2018Alcohol used as a "weed killer" optimizes the harvest of ambrosia beetles.

If on a warm summer's evening in the beer garden, small beetles dive into your beer, consider giving them a break. Referred to as "ambrosia beetles", these insects just want what’s best for themselves and their offspring. Drawn to the smell of alcohol in the cold liquid, the beetles are always on the lookout for a new environment to farm. And alcohol plays an important role in optimizing the agricultural yield of their crops, as an international team of researchers reports in the current issue of the journal PNAS.

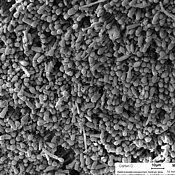

The black timber bark beetle and its fungal "crop"

Ambrosia beetles, which are a large group of several thousand species worldwide, belong to the bark beetles. All species are characterized by the ability to cultivate fungi. The researchers, including Peter Biedermann, from the Department of Animal Ecology and Tropical Biology at the University of Wuerzburg and the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Christopher Ranger (Ohio State University, USA), as well as Philipp Benz from the Wood Research Institute of the Technical University of Munich (TUM), investigated the role played by alcohol in the farming of fungi as practiced by the black timber bark beetle and its fungal "crop".

"It has long been known that alcohol is produced by weakened trees and that these trees are recognized and colonized by ambrosia beetles," says Biedermann. Baiting traps with alcohol is a classic way to catch these bugs. "And often you will find the roughly two millimeter long beetles in glasses of beer, when a beer garden is surrounded by old trees," adds Biedermann.

Sustainable agriculture as a recipe for success

Thanks to the results of Biedermann, Ranger and Benz, we now know why alcohol is so attractive to these insects. "An increase in the activity of alcohol-degrading enzymes allows the insects' fungi to grow optimally in alcohol-rich wood, while alcohol is toxic to other microorganisms," says Biedermann. More fungi mean more food for the beetles, and more food means more offspring. The beetles and their larvae feed on the fruiting bodies of the fungi, which grow best at an alcohol concentration of about two percent.

"At this level of alcohol, the omnipresent molds, which can also be considered the "weeds" of fungal agriculture, only grow weekly and cannot overgrow the fungal gardens”, says Prof. Benz. Given the beetle’s evolutionary success, the details of its sustainable farming strategy are worth noting. "For more than 60 million years, the animals have successfully and sustainably practiced agriculture, even though their crop – the ambrosia fungus – is a monoculture." Unlike human farmers, the insects seem to have had no problem with weed fungi becoming resistant to the alcohol.

Communal care of fungal gardens

It is not only the agricultural skill of the Ambrosia beetles that inspires Biedermann. "They show social behavior," says the ecologist. Beetles share the work of cultivating their fungal gardens: some clean the tunnel systems that are being eaten into the wood, others clear the dirt from the nest and clean their fellow workers – always with the aim of optimizing the symbiosis of beetle and fungus.

This system is so sophisticated that when they colonize new trees, the animals bring along the fungal spores in their own spore organs. New fungal gardens grow from the "transplanted” spores. The fungi are even able to produce alcohol in order to optimize their environment.

"This way, the fungi cultivated by the ambrosia beetles behave like beer or wine yeasts, generating an alcoholic substrate in which only they can thrive and from which other competing microorganisms are excluded," explains Biedermann.

There is much more to learn from the beetles

Biedermann and Benz are planning to collaboratively study these bark beetles and their fungal symbionts also in the future. One of the many open questions that remains about the lifestyle of these six-legged friends and their fungal "crops” is: what exactly enables them to survive in this boozy environment? "Of course, they have to be more resistant to alcohol than other creatures," says Biedermann. "These characteristics are also of high potential interest from a biotechnological point of view, since they might be transferrable to other systems when better understood”, adds Benz. Maybe humanity has something to learn from the bark beetle after all.

"Symbiont selection via alcohol benefits fungus farming by ambrosia beetles " by Christopher M. Ranger, Peter H. W. Biedermann, Vipaporn Phuntumart, Gayathri U. Beligala, Satyaki Ghosh, Debra E. Palmquist, Robert Mueller, Jenny Barnett, Peter B. Schultz, Michael E. Reding & J. Philipp Benz. Published in PNAS, DOI: www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1716852115.

Contact:

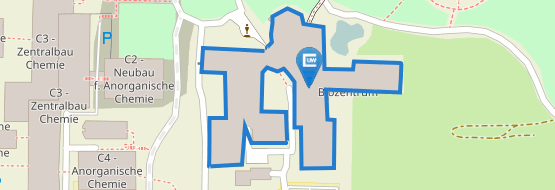

Dr. Peter Biedermann, Biocenter, Department of Animal Ecology and Tropical Biology (Zoology III).

T .: +49 (0) 931 31-89589, peter.biedermann@uni-wuerzburg.de, More: http://www.insect-fungus.com/

Prof. Dr. J. Philipp Benz, Professorship of Wood Bioprocesses, Holzforschung München, Technical University of Munich. T.: +49 (0)8161 71-4590, benz@hfm.tum.de, working group: Link